When Anxiety Has a Floor Plan

How to See an Assemblage

In the most recent Radical Therapist Podcast on new materialisms, I told a story were a heterosexual couple I was working with came in and sat down and the male partner proceeded to set his phone down, face down. This action immediately created tension when the his partner asked him why he set it down face down. The phone was now an active agent in the relationship. It was an eye opening moment for me.

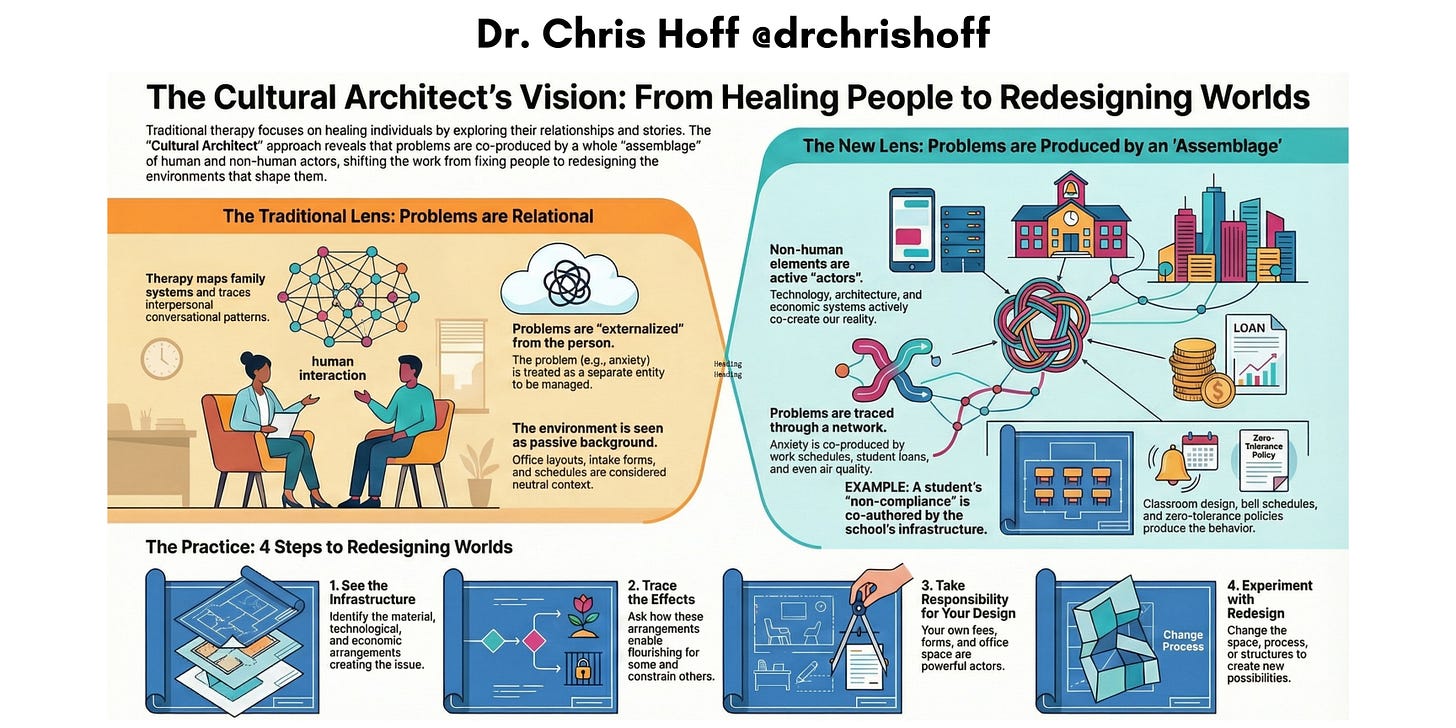

I’ve been throwing around this term, Cultural Architect, for a while now, talking about designing conditions for collective flourishing, about moving beyond individual healing toward systemic transformation. But I haven’t been heavy on specifics of how one actually develops this capacity. So here’s what I’m doing. Over the next several posts, I’m going to expand on the Six Ways of Seeing that I believe are foundational to Cultural Architect work. These aren’t techniques or interventions. They’re perceptual shifts, ways of training your attention that make different kinds of work possible.

My hope is that you’ll take these ideas and run with them in your own direction. Cultural Architecture isn’t a model to adopt. It’s an orientation you develop, adapted to your own context, your own communities, your own vision of what becomes possible when we stop limiting ourselves to healing individuals and start designing the conditions in which collective flourishing emerges. This first post focuses on systems thinking, but not the systems thinking you might already know. This is about radicalizing our understanding of systems to include the more-than-human world.

I used to think I was pretty good at systems thinking. My PhD is in Marriage and Family Therapy which was really getting a PhD in systems theory and relational practice. I could map a family system, trace interpersonal dynamics, notice who spoke for whom. I’d learned from the greats, Bateson’s cybernetics, White and Epston’s externalizing conversations, the whole narrative therapy lineage that taught us problems aren’t in people but produced in the larger social/cultural context.

But then I discovered the work of Bruno Latour and realized I was still missing half the system.

Actually, more than half.

What I Didn’t See

Here’s what I couldn’t see, The intake form sitting on my clipboard was actively shaping the story before anyone spoke. The furniture arrangement was determining whose body could be comfortable and whose couldn’t. The 50-minute hour was producing a particular kind of temporality that made certain conversations possible and others impossible. The self diagnosis many people carried in with them, was not a neutral description but an active force organizing the narrative around pathology. Setting the phone face down. These weren’t just background context. They were actors, entities that were doing things, making things happen, producing effects.

This is where Bruno Latour and his actor-network-theory gave me a way forward.

Following the Action

Latour’s move is deceptively simple, stop deciding in advance what counts as an actor. Instead, follow the action. Ask, what’s making things happen here? What’s producing effects? What matters? When you do this in a therapy room, everything changes. A client comes in struggling with anxiety. In a traditional narrative therapy approach, I might externalize the anxiety, give it a name, explore its tactics, trace its effects on relationships, investigate its history. This is powerful work. It shifts the problem from internal deficit to external entity that can be related to differently. Often agency in the face of it can be found. But what if we kept going?

What if we traced how the anxiety is being co-produced by the entire assemblage:

The open floor plan at work that provides no refuge from constant surveillance

The phone that pings with urgent messages at all hours

The health insurance that requires documented productivity to maintain coverage

The student loan payment that arrives regardless of wellness or ability to pay

The air quality in the apartment that affects sleep

The shift schedule that violates circadian rhythms

The intake form that demanded a linear trauma history in the first session

These aren’t metaphors. They’re not “contributing factors” that orbit around the real problem. They’re co-authors of the anxiety, participants in its ongoing production.

The Narrative Therapy Lineage

This isn’t a rejection of narrative therapy, it’s an extension of it. Michael White and others taught us that problems are relationally constituted. That nothing exists in isolation. That the same story told in different relationships produces different effects. That we’re always working with how meaning gets made in interaction. What Latour and the new materialists add is this: those interactions aren’t just between humans.

We’re entangled with technologies, architectures, documents, economic systems, material objects. These entanglements are producing the stories we’re trying to shift. And when we ignore the non-human actors, we leave half the story-making apparatus untouched.

A Different Kind of Externalization

Traditional externalization: “The anxiety is not you. It’s something you have a relationship with.”

More-than-human externalization: “The anxiety is being produced by an entire assemblage of human and non-human actors. Let’s trace who and what is participating in its production.”

This changes the practice. We’re not just restructuring the person’s relationship to the problem. We’re redesigning the assemblage that’s producing the problem.

What This Looks Like in Practice

Let’s say a therapist was working with a teenager described as “non-compliant” by his school. They did beautiful narrative work, found exceptions to the compliance story, thickened alternative narratives, connected him with witnesses who saw different possibilities.

But the kid kept getting suspended.

Then the therapist started mapping the non-human actors. The classroom was arranged so all students faced the teacher, no peer interaction possible. The schedule required transitioning between seven different classrooms in four-minute intervals. The online grading portal meant his parents received real-time notifications of every missing assignment. The zero-tolerance behavior policy left teachers no discretion. The metal detectors at the entrance communicated who was dangerous from the moment of arrival.

The “non-compliance” wasn’t just a story about this kid. It was being produced by an entire infrastructure, an assemblage of architectural decisions, scheduling systems, technological surveillance, and punitive policies that made compliance nearly impossible for anyone whose body or brain worked differently than the design assumed.

The practice shifts from changing the kid’s story to changing the infrastructure.

Designing the Conditions

This is where Cultural Architecture emerges from narrative therapy. Narrative therapists have always known that the conversational space matters, that the questions we ask, the documents we create, the audiences we assemble all participate in story development. We’ve just been focusing primarily on the conversational and discursive dimensions.

But what about the material dimensions?

What stories are being produced by:

Where you locate your practice and who can access it

How you structure intake and what it establishes as relevant

What your space looks and feels like and whose bodies it accommodates

How you document and what systems of power you’re feeding

What your fee structure is and who it includes or excludes

How you schedule time and what rhythms you’re imposing

These aren’t neutral background. They’re infrastructure. They’re the material conditions in which certain stories become possible and others don’t.

The Practical Question

So here’s where I land. If problems are produced by assemblages of human and non-human actors, then intervening in problems means redesigning assemblages. This doesn’t mean therapists need to become urban planners or policy experts (though some might). It means we need to:

1. See the infrastructure

What material, technological, spatial, temporal, economic arrangements are participating in producing the situations we’re addressing?

2. Trace the effects

How are these arrangements distributing capacity? Whose flourishing do they enable? Whose do they constrain?

3. Take responsibility for what we design

The spaces we create, the forms we use, the documentation we produce, the fees we charge, these aren’t neutral. They’re designing conditions. We’re accountable for them.

4. Experiment with redesign

What becomes possible if we configure things differently? If we change the intake process, restructure the space, document differently, challenge the temporal constraints?

The Invitation

This way of seeing is destabilizing. Once you start noticing non-human actors, you can’t unsee them. The therapy room will never look neutral again. The intake form becomes suspect. The scheduling software reveals its assumptions. The diagnostic manual shows its violence. But this isn’t paralysis. It’s possibility. Because if problems are produced by assemblages, then we can redesign assemblages. We can intervene not just in stories but in the material-semiotic infrastructures that shape what stories become possible. We can become, as Arturo Escobar puts it, designers of the conditions for collective flourishing. That’s what Cultural Architecture is. And learning to see systems this way, as more-than-human assemblages, is the first of six ways of seeing that makes this work possible.

Peace.

For more check out my latest podcast. In this episode of The Radical Therapist, I sat down with systemic therapists and thinkers Christopher Loh and Federico Albertini to explore how New Materialisms are reshaping the foundations of therapeutic practice. What happens when therapy loosens its grip on language as the primary site of meaning-making, and begins listening to the material, the more-than-human, the in-between.

Hi Chris - I'm a first year MFT student who enjoyed your talk at the Narrative Therapy Conference this November and have been following your posts since!

Taking non-human forces into account reminds me of animist traditions, which were rarely concerned with individual, internal forces but gave significant credence to external forces - nature, community, seasons. Externalization with anxiety takes the pressure off in the sense that the anxiety isn't synonymous with you, but there can still be an individual sense or 'responsibility' for it, or needing to handle it. The assemblage view seems to peel individual ownership back even further.

I'm curious what this perceptual shift means for 'responsibility'?

Wild how once you start noticing the non-human actors, the whole room starts confessing. The phone has opinions, the intake form has an agenda, the floor plan is basically running its own shadow government.

Feels like half our anxiety isn’t living in our bodies at all. It’s living in the architecture, the policies, the pings, the systems that tell us who we’re allowed to be before we even speak.

Blessed be the ones who stop blaming themselves long enough to see the machine.