Beyond Community

The Case for Coalitional Thinking in Therapy and Social Life

“The idea of community is without doubt the liberal equivalent of the conservative notion of ‘family values’ – neither exists in contemporary culture, and both are grounded in political fantasy.”

—Coalitions, Not Communities, Critical Art Ensemble

A couple of years ago, I posted that quote from the Critical Art Ensemble on the Radical Therapist Instagram page. The post struck a nerve. It sparked questions, curiosity, and quiet agreement. For many, the quote rang true, naming something they had felt but hadn’t quite articulated. It also provoked a deeper tension: How can we be critical of community when so many are suffering from isolation, disconnection, and the ache for belonging? That question has stayed with me.

The allure of community runs deep. It brings up images of warmth, shared meals, common language, a sense of belonging. In a fragmented world, community is often imagined as the antidote, something to return to, recover, or build from scratch. For many of us, it’s even become a moral good, a kind of unquestioned horizon of therapeutic and political work. We seek to “build community,” “find our community,” “heal in community.”

And yet, as the Critical Art Ensemble reminds us, the very idea of community can function as a political fantasy not unlike the conservative trope of “family values.” In both cases, what’s being invoked is not the messiness of real relationships but a kind of imagined coherence. A purity. A center that must be protected. And therein lies the trouble.

The Problem with Community

While community can indeed be a site of care and connection, it can just as easily become a site of exclusion, surveillance, and conformity. Communities, especially when idealized, often become gatekeepers of belonging. They ask: Are you enough like us? Do you share our values, our language, our trauma, our rituals? Have you earned your place here? In therapeutic settings, this plays out in subtle ways. Clients speak of being “othered” by the very groups they hoped would hold them. In these moments, community reveals itself not as a refuge but as a boundary, a line drawn to protect an ideal rather than support complexity.

One-World Worlding and the Capture of Community

Arturo Escobar speaks of one-world worlding, the process by which a single worldview, often Western, modern, and colonial, is imposed as the default reality. Under this paradigm, plurality is flattened. Alternatives are erased or made to assimilate. Community, when idealized, often becomes a mechanism of one-world worlding. It creates the illusion of a singular way to relate, to belong, to heal. Even well-intentioned “inclusive” communities can end up reproducing monocultures of belief and behavior. They demand consensus where coalitional politics might be more appropriate. What gets lost is the pluriverse: the understanding that many worlds, many ways of being and knowing, coexist, and must coexist for any just future to emerge.

The Coalition as a Pluriversal Practice

Coalitions, by contrast, assume difference. They are not based on shared identity, but on shared stakes or matters of concern as Bruno Latour would say. They make room for partial agreement, temporary alignment, and ongoing negotiation. Coalitions are pragmatic. They know we may not worship the same gods, use the same pronouns, or vote the same way, but we might still have a common interest in resisting extraction, surviving climate catastrophe, ending violence, or dismantling systems of domination.

In therapy, adopting a coalitional mindset invites us to shift the questions we ask our clients. Instead of “where is your community?” or “where do you fit?” we might ask:

Who are your current allies, even if only temporarily?

What collaborations are possible in this chapter of your life?

Where can solidarity emerge without demanding sameness?

How can you create coalitions of care that reflect your own becoming?

This orientation honors the multiple, the partial, the emergent. It resists the gravitational pull of purity politics, which so often derail healing and growth. It acknowledges that some of the most powerful connections are built not in shared identity but in shared commitment.

From Belonging to Aligning

The move from community to coalition is not about giving up on belonging, but about reimagining it. Belonging, in a coalitional frame, becomes something negotiated rather than inherited. It’s not about finding your one true home, but about co-creating space where you can act, feel, and be with others who may not be like you, but are walking alongside you, for now.

Coalitions are dynamic. They bend, stretch, morph, dissolve. They require trust without uniformity, purpose without permanence. They are, in this way, deeply relational, but not in the tidy, sentimental sense we often assign to the word “community.”

A Therapeutic Call to Coalition

As therapists, we would do well to embrace this shift. Our clients are navigating a world where identity is increasingly fragmented, where algorithms promise affinity but often deliver isolation, and where the longing for “community” is frequently met with performance, posturing, or rejection.

By inviting a coalitional imagination, we help clients build resilience through difference, rather than against it. We help them form networks that reflect the fluidity of their lives, rather than holding them to static standards of belonging. This is not to say that all communities are harmful, or that coalition is easy. But if we are serious about cultivating lives and worlds that can hold multiplicity, we must begin to practice the art of alignment over assimilation.

In a pluriversal future, it won’t be the strongest communities that lead the way. It will be the most agile coalitions, the ones capable of holding paradox, difference, and commitment in the same breath.

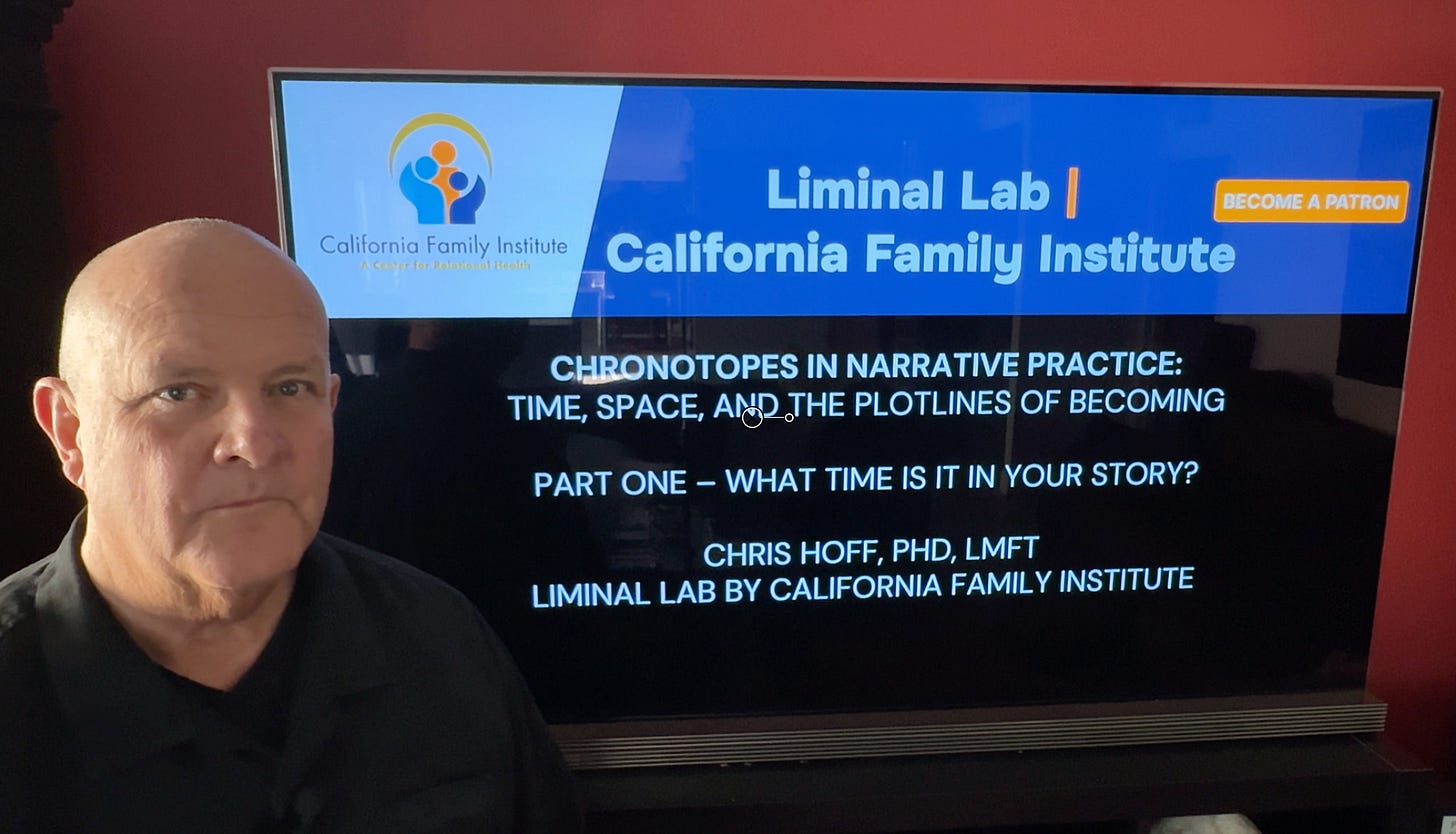

Speaking of community :) Have you been to the new Liminal Lab by California Family Institute site on Patreon yet? I just started a new series on Chronotopes in Narrative Practice. Support a good cause and learn creative and innovative ways to work with those that seek your help. Join us

Peace.